Black New Mexicans Speak Up: Elders Project Reclaims Space In New Mexico's Story

Learn more about the Baldwin-Emerson Elders Project and access oral histories from 27 New Mexican Black elders.

by Kristin Satterlee

What does it mean to be a Black New Mexican? How does one make sense of that identity in light of our state’s tricultural myth: the story that New Mexico history revolves around Latine, Indigenous, and Anglo heritages in a way that tends to erase everybody else?

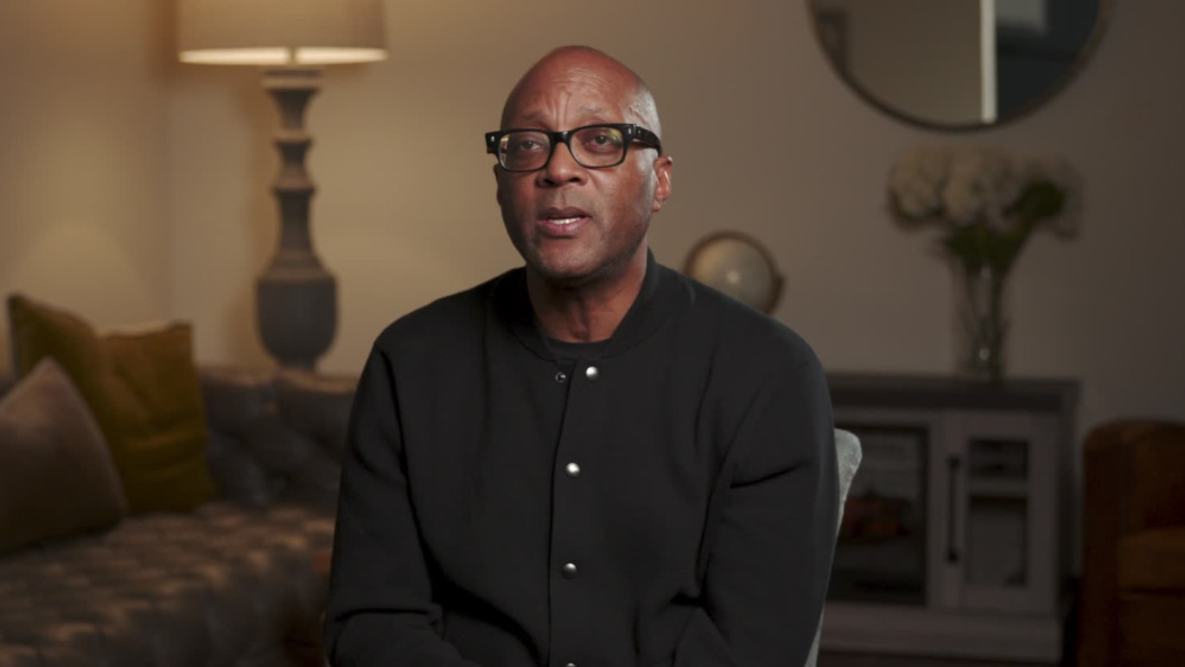

Or, in Ellery Washington’s words, “How can you be Black and New Mexican in a place that says you don't exist as a central part of the culture?”

Lessons from our elders

As one part of the Baldwin-Emerson Elders Project, Washington brings forward an important piece of this puzzle: oral histories from 27 New Mexican Black elders. The nationwide Elders Project includes stories from ten underrepresented US communities of color, including Latina lesbian elders, Indigenous storytellers, and the Texan descendants of the original celebrants of Juneteenth.

Washington was born and raised in Albuquerque, graduated from the Sorbonne in Paris, and now teaches at the Pratt Institute in New York. When he heard the call for writers to collect oral histories for the Elders Project, he knew there were important lessons held by the Black elders of New Mexico.

Who is a New Mexican?

Some of those lessons lay in the elders’ answer to the question, “Do you consider yourself a New Mexican?” Most, but not all, said they did identify as New Mexicans. But many still spoke about “the absence of declared African American cultural experience” in their home state.

“I was asking my elders to help me answer a question I think I had been trying to answer for a very long time,” Washington says. He felt it as a child, when his sixth-grade teacher couldn’t identify his place in the state’s cultural history. The principal brought up Ellery’s question at an assembly in front of the whole school, telling the students that “white people brought [Black people] to this country as slaves, and therefore we're kind of part of the Anglo culture.”

There were more things wrong with that than young Ellery could begin to comprehend, but “I knew that it was wrong and it felt bad…. I don’t think that experience ever left me.”

The power of story

It would have helped him then, Washington says, to have resources. Stories. “If I… could have gone online and typed in African American New Mexicans or Black New Mexicans or whatever, and something interesting and fun and lively showed up… I wouldn't have had to rely on other people to say that I—that we exist.”

Washington has made many hours of Black New Mexican oral history available for us all. Check it out at bit.ly/nmeldersproject.

Black history in the classroom

He’s also taking it a step further, working with a team to create educational modules. Students studying New Mexican small business, for instance, can hear “Janice Washington talking about her family starting this [dry-cleaning] business” and see a picture of her family inside it.

Stories are powerful. “Every voice matters. Finding out who's not being heard and elevating those voices elevates us all.”